Bruce Nauman

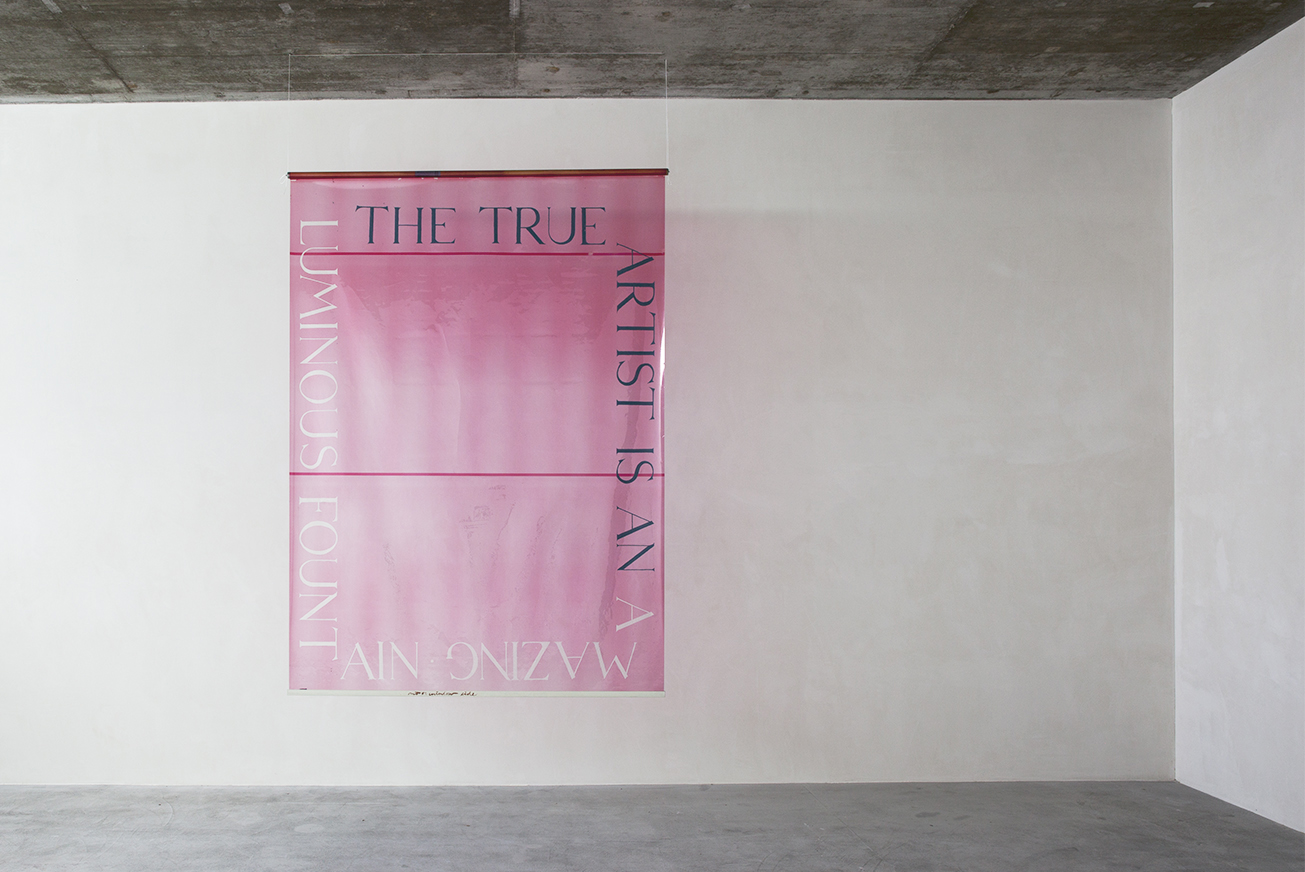

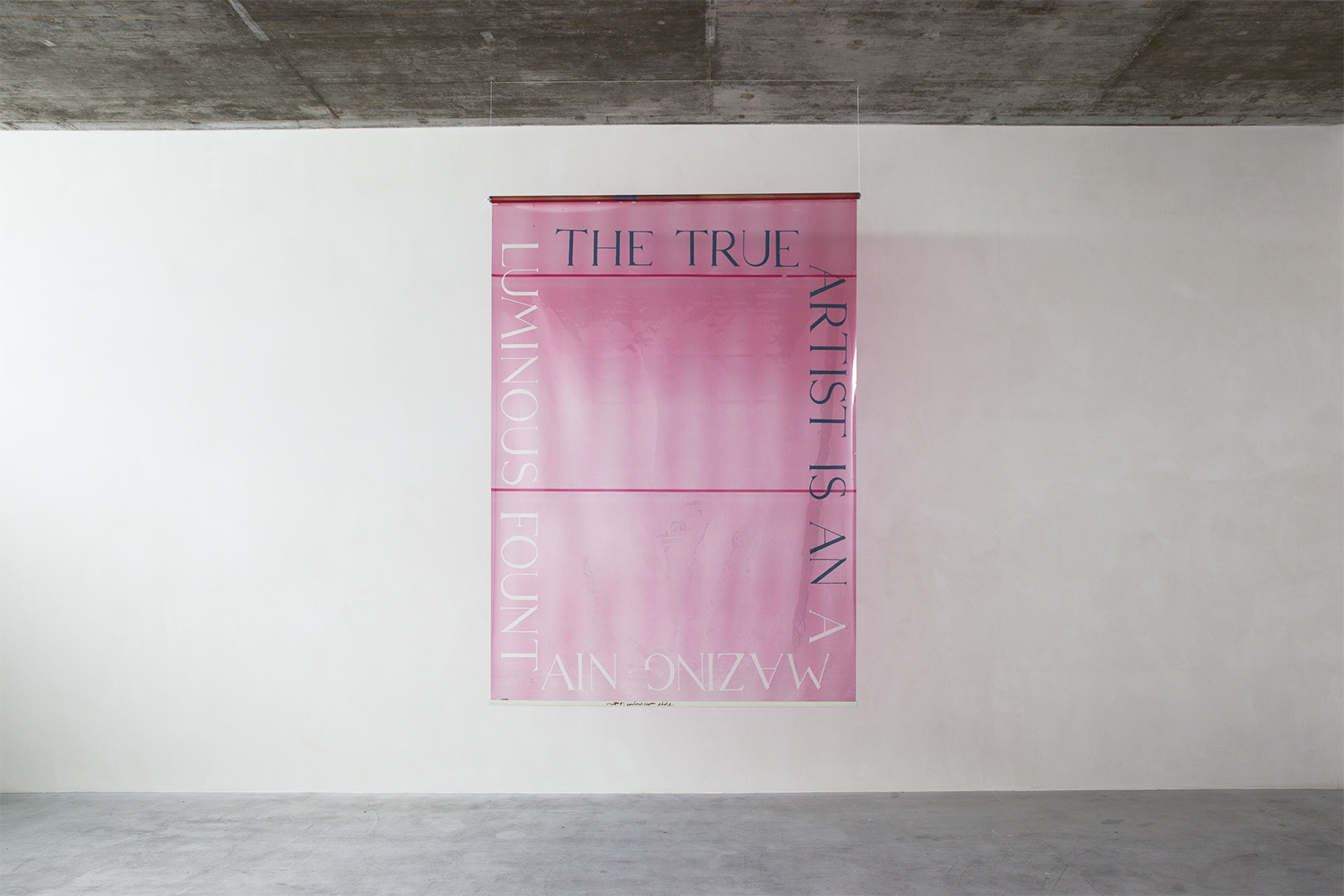

The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain (Window or Wall Shade), 1966

Transparent rose-coloured Mylar

96 x 72 in. (250.5 x 179.5 cm)

cat. rais. 58

by Christel Sauer

© Bruce Nauman / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Fabio Fabbrini, © Raussmüller.

In June 1966 Bruce Nauman completed his Master of Fine Arts at the University of California in Davis. He had initially also studied mathematics and physics and had thereby become aware that he was an artist. His unconventional sculptures of fibreglass and polyester resin attracted attention at an early stage, and he was given his first solo show at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery in Los Angeles even before completing his MFA. Nauman was also aware that, as an artist, he had the freedom to decide on what he did. It was not entirely clear to him, however, how he should proceed. Having left the stimulating environment of college, he felt very cut off. From Davis Nauman moved to San Francisco, where he had been given a teaching contract and where he rented a former grocery store as a studio and an apartment. He was not yet 24 and had been married for two years to Judy Govan, who in August 1966 gave birth to their son Erik. In an interview with Ian Wallace and Russell Keziere twelve years later, Nauman described his state of mind at this time. Asked by Keziere how he perceived himself and his role in the expanding art world, Nauman gave a reply that has since been cited, not without reason, on many occasions. It offers a key to Nauman’s understanding of art, and its validity extends far beyond his difficult beginnings in San Francisco. It shows Nauman’s self-assurance as an artist and the importance that he attached from an early date to structured activity – more than to the resulting objects. It reflects the coherence of his thinking and the astonishing openness of his approach. And above all, it demonstrates the self-honesty which is so central to the cogency of his entire oeuvre.

“When I left school and got a job at the Art Institute in San Francisco, I rented a studio space. I didn’t know many people there, and being a beginning instructor I taught the early morning classes and consequently saw very little of my colleagues. I had no support structure for my art then; there was no contact or opportunity to tell people what I was doing every day; there was no chance to talk about my work. And a lot of things I was doing didn’t make sense so I quit doing them. That left me alone in the studio; this in turn raised the fundamental question of what an artist does when left alone in the studio. My conclusion was that I was an artist and I was in the studio, therefore whatever it was I was doing in the studio must be art. And what I was in fact doing was drinking coffee and pacing the floor. It became a question of how to structure those activities into being art, or some kind of cohesive unit that could be made available to people. At this point art became more of an activity and less of a product. The product is not important for your own self-awareness. I saw it in terms of what I was going to do each day, and how I was going to get from one to another […]. What you are to do with the everyday is an art problem. […] An artist is put in the position of questioning one’s lifestyle more than most people. The artist’s freedom to do whatever he or she wants includes the necessity of making these fundamental decisions.” When Keziere observed to Nauman that these speculations on his role and behaviour as an artist were “not aesthetic but moral”, Nauman agreed that this was right.1

In a later interview with Joan Simon, Bruce Nauman stressed the importance of moral – or ethical – awareness, when he said: “Art ought to have a moral value, a moral stance, a position.”2 And in the same conversation in a different context: “I think that being an artist does involve moral responsibility.”3 Nauman’s understanding of the artist as one who conveys convictions is clearly palpable here. This understanding of art runs through his entire oeuvre. The true artist expresses what is and how he experiences it. He responds, as an affected individual, to the circumstances with which he finds himself confronted, and what he does and how he shapes his actions corresponds to his picture of the world and himself. His art is the translation of his perception and its associated feelings – the result of the existential challenge to give his personal insights, actions and feelings a form which will render them intelligible for others. A number of deeply affecting, in some cases even disturbing works have grown out of Nauman’s awareness of this responsibility.4 They allow us to divine the state of mind from which they issued; what is more, they transfer it to us. A look back over Nauman’s oeuvre as a whole shows to what extent this artist has taken the motivation for his art from his experience of human behaviour, as well as from a relentless interrogation of his own role in the context of what he has directly or indirectly experienced. The life-long earnestness with which Nauman has actively pursued this question – his “moral” stance – is a powerful argument for the validity of his art.

The grocery store that Bruce Nauman rented in San Francisco’s Mission District, in order to use it as a studio, had large shop windows facing the street. From pictures taken by the photographer Jack Fulton, we can see that Nauman painted the windows with paste and stuck sheets of paper over some of the glass in order to restrict the view from outside. Out of the practical necessity of shielding his studio from the sun’s glare and affording himself some privacy, coupled with the need to manifest himself as an artist, Nauman created a work with an unusual dual function: a semi-transparent Window or Wall Shade, with which he could protect himself from the direct gaze of passers-by and at the same time hang a message in the storefront window.

Nauman bought a standard multi-stop roller blind measuring 8 feet long and 6 feet wide and consisting of three horizontally-joined sheets of pink-coated Mylar, a polyester material that is also used in the printing industry. He made this blind the support for a statement about the nature of the artist: around its edges he wrote, in an attractive serif font, the sentence THE TRUE ARTIST IS AN AMAZING LUMINOUS FOUNTAIN.5 He painted the 17 letters of first five words in black on top of the Mylar, and carefully scraped the 23 letters of the last three words out of the coating with a knife, so that the elegant font stands out pale and transparent against the rose-coloured ground. The capital letters, 7 inches high, surround the inner rectangle in the style of an epitaph. The effect is almost dignified and presents a bizarre contrast to the pink plastic blind – just as does the cryptic message of the text.

As a standard model, Nauman’s Window or Wall Shade is attached at the top to a slender wooden roller 1 ¼ inches in diameter, and is weighted at the bottom by a metal bar. In the middle of this bar, Nauman has written the note “out on window side” and “in” on the reverse. If the Mylar shade were hung in the window, the text would thus be legible from the street. In order to decipher it, however, it is necessary to change position, since along the lower edge the words are written upside down, while on the right-hand side they face inwards and on the left-hand side, outwards. Nor do they run consecutively, but jump from the middle of the lower edge back up to the top. Nauman plays here with reversals, with the switch between inside and outside, front and back – just as he had already done in his sculptures – and in so doing heightens the disconcerting effect of the statement. It seems as if, in this work, the blocking of the physical gaze at the same time wishes to encourage scrutiny at a more abstract level – something along the lines of: if you look more closely, you will see that the artist brings forth something astonishingly illuminating. Much more than actually seeing inside the studio, it would have been reading the statement about the “true artist” that told passers-by what they were dealing with in this location. In the end, however, Nauman never placed the work in the store window, but hung it on his studio wall, where it provided a source of encouragement primarily for himself.6

Reproduced in: Peter Plagens, Bruce Nauman: The True Artist, London, Phaidon, 2014, no. 42, p. 48. Photo: Jack Fulton, © Jack Fulton / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich.

The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain is the first major piece in which Bruce Nauman worked with the medium of text. Shortly beforehand he had made a small, convex lead plaque bearing a quotation from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (1953) – the concise statement of an irrefutable truth: A Rose Has No Teeth.7 The plaque was intended to be mounted on a tree trunk and over the course of time become overgrown by vegetation and hence invisible. In the case of the window blind, on the other hand, the aim was clearly that it should be perceived. Like a confession, it proclaims Nauman’s interest in language and meaning – in making statements that are all the more challenging because their substance cannot immediately be deciphered. With its text, the pink Mylar shade stands at the start of a series of works, many of them neon objects, in which Nauman operates with words and phrases that spark trains of thought in the viewer’s mind. They are often verbal puns, including palindromes such as Raw War8 – or confrontational “lists of human attributes and actions”.9 The early Window or Wall Shade delivers its message more discreetly than the colourful neon signs which succeed it, and also more poetically and enigmatically, but it serves Nauman’s intention to impact on the viewer’s consciousness with no less resolution.

Bruce Nauman has never said how he arrived at the mysterious wording of the artist as a luminous fountain. According to Coosje van Bruggen in her Nauman monograph, the artist “liked the fact that the phrase is vague, seeming to convey meaning but actually making only the most metaphorical kind of sense.”10 But perhaps Nauman, as a passionate reader, had also come across the writings of Jalal ad-Din Rumi, the influential 13th-century Persian poet and Sufi mystic.11 Rumi’s “luminous poetry”12 had never been forgotten, but in the 1960s and 1970s it enjoyed a renaissance in the West as part of a broadening search for meaning. Rumi’s richly figurative writings, which in the original Persian are said to possess the captivating sound of melodious music, were translated into English in various editions and sold widely within the Anglo-Saxon sphere.13 One of Rumi’s Odes, titled Become a Sea, contains the following lines: “Do not grieve that every form you see, every mystical truth you hear will one day vanish. The Fountain is always gushing water. Neither Fountain nor water will ever stop flowing, so why mourn? Your spirit is a fountain; river after river flow from it …”.14

© Bruce Nauman / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler.

The possibility that Nauman was influenced by writings such as this is strengthened by another work, created shortly after the Mylar shade and likewise intended to proclaim a message about the “true artist” as a window or wall sign: a red and blue neon spiral in the style of an advertising logo with the text The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths.15 These “mystic truths” – relatively impenetrable in the shape of the neon sign – take on a certain meaning in conjunction with Rumi’s ode. One could say: it is the truths that underlie all which find expression in art and which give the creations of the true artist their timeless significance. Whether the artist thereby helps the world is open to question, but he undoubtedly enriches it, and perhaps he opens up new ways of seeing and new insights. Whatever the case, it is interesting that Nauman appropriated both the image of the gushing fountain and the mystic truths and associated them with the artist, that is to say himself; and that he granted them not to all, but only to the “true” artist: the one who brings forth, out of himself, something that possesses an illuminating validity.

With his notion of the artist as the bringer of insights, Nauman is not alone. In his influential Sentences on Conceptual Art, published in 1969, Sol LeWitt states in the first sentence: “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.”16 For LeWitt, conceptual artists are those for whom “the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work”17. Thanks to their intuitive abilities, artists can bring forth ideas that are often conclusions, or which lead to them; like a fountain – to continue the metaphor – they can thus produce a river. “In terms of ideas,” says LeWitt, “the artist is free even to surprise himself”.18 An artist often knows neither where an idea has come from nor where it is leading. He is interested above all in the question of how to arrive at an idea that takes him forward. This was a core issue for Bruce Nauman. He said: “… most of my work is to some degree about how anybody continues to make art. It’s always interested me how one does any work in the studio at all, what it’s supposed to be about, how you get things started or make any sense out of the process. Even though the work is coming from somewhere inside, you can’t put your finger on the source”.19

In the case of Nauman’s Mylar shade, the source of the idea seems obvious: the artist’s understandable desire to block the direct view through the store windows from the outside and to screen off the private sphere within. But this purpose could also have been served by the roller blind as such – even if, strictly speaking, the transparency of its material offers no real visual protection and its pink colour does more to attract than repel the eye. The quality of Nauman’s works, however, derives not from their unconventional use of a utility object per se, but from the precision with which the object is repurposed in a strange and unfamiliar way – in this case as the support for a complex and disconcerting message. The potential that furnishes Nauman’s works with significance lies in the intelligence with which they combine planes that have nothing to do with each other in themselves, but which in their association generate a holistic intensity. In order to succeed, i.e. to achieve an intensity that conveys itself to the viewer, the works need a finding at their source: the plausible yet surprising “conclusion” (LeWitt) that gives meaning to the activity of the artist. And here lies the crux. For ideas often spring from a kind of illumination, and this latter cannot be induced. Bruce Nauman has repeatedly suffered times when no useful ideas have come to him and he hasn’t known what to do in his studio. The way in which he repeatedly starts afresh with a new idea, whose implementation in turn demands a different approach and different materials and techniques, and thereby often results in unexpected forms of manifestation, is what distinguishes Nauman from the many artists who, having once adopted an idea, make it the safe foundation upon which to build and expand their oeuvre.

The “illumination” for the concept of Nauman’s Window or Wall Shade came from an object in his immediate surroundings: Nauman suddenly recognised the effectiveness of a neon beer sign, which still hung in the window of his studio from its past as a grocery store.20 In its candid utility, it sowed in him the idea of giving the roller blind and subsequently the neon spiral the effect of display signs. “It was the idea that they would be signs just like any other sign, like a beer sign […] something like that …. I think a store sign, anything, it could hang in a window or on a wall or whatever.”21 To communicate an unusual message in the style of a common product advertisement will have appealed to Nauman, not least on account of the tension arising out of the discrepancy between form and content. It also gave him the opportunity to make a personal statement public – something that makes the Mylar shade a forerunner of Nauman’s later explorations of the private/public theme. Most importantly of all, however, the idea corresponded at that time to Nauman’s aim to produce art that did not necessarily look like art. In a conversation with Brenda Richardson, who in 1982 organised the first exhibition of his neons, Nauman said of his window signs: “I had an idea that I could make art that would kind of disappear – an art that was supposed to not quite look like art. In that case, you wouldn’t really notice it until you paid attention. Then when you read it, you would have to think about it.”22

As a test, Nauman hung the True Artist neon spiral in his front window for a while, on public display next to the beer sign. There is no evidence that it produced any reaction; perhaps it genuinely didn’t stand out among the other advertising media. Whatever the case, for Nauman himself the luminous sign was an experience which fed into his following works using neon. The Mylar shade, by contrast, remained a one-off in its appearance – unlike in its written content. It set in motion, in Nauman’s oeuvre, a development which gave a first form to the literal addressing of the recipient, and which stands at the start of a wealth of written and spoken text-based works. The fastidious creation of the Window or Wall Shade by hand, however, elevated it to a plane where the principle of simple distribution no longer applied. In contrast to the artist’s neon works, which could be easily manufactured in multiples, Nauman’s hand-lettered roller blind did not allow reproduction.

© Bruce Nauman / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Fabio Fabbrini, © Raussmüller.

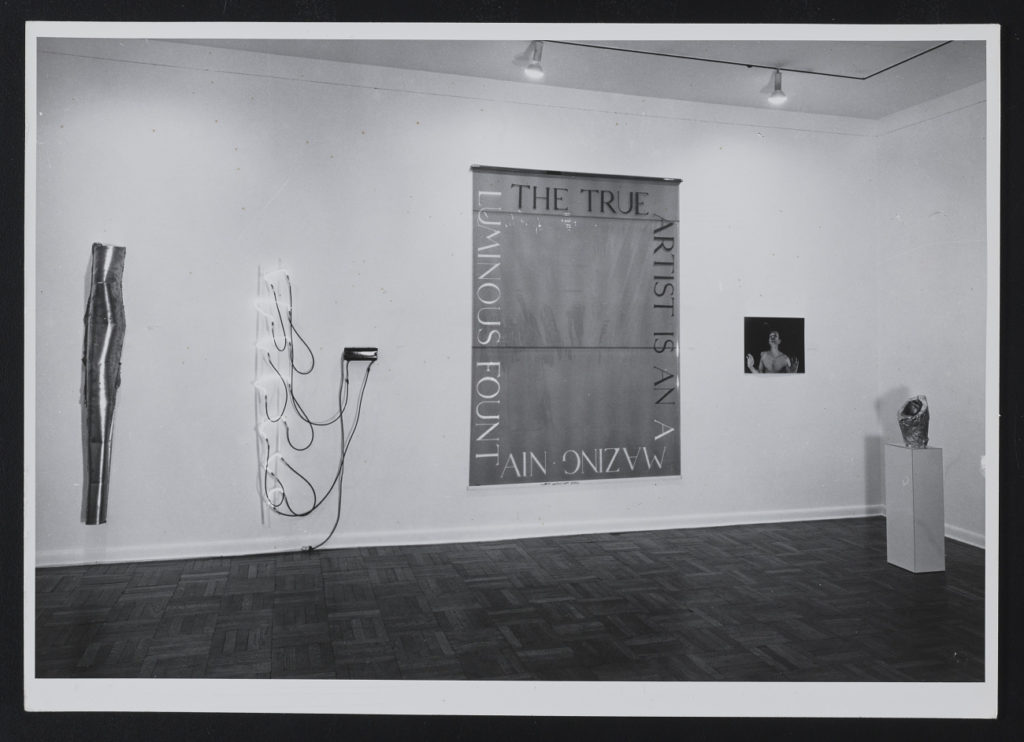

It is variously stated that Nauman hung the pink Mylar shade in his studio window next to the neon spiral, but this was not the case, as Nauman has confirmed. 23 Only many years later was the Window or Wall Shade displayed in front of windows, primarily in the context of museum exhibitions. In 1981, for example, it was installed in this way at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld24 and subsequently in a solo show at the Zurich gallery of Konrad Fischer, who represented Bruce Nauman in Europe from 1968 onwards. Urs Raussmüller purchased the work and as from 1984 showed it for many years in the Hallen für Neue Kunst, Schaffhausen, in company with other major Nauman pieces. Previously, the shade was hung on a wall not only in the artist’s San Francisco studio but also at his 1968 exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery (Nauman’s first occasion for a trip to New York), even if it is listed in the catalogue as Window Screen. Nauman himself also spoke of the work as a “window-shape wall sign”.25 A photo by Jack Fulton shows the artist in his studio with the Mylar shade hanging on the wall. A similar image appears in Shelby Kennedy’s short film The Bruce Nauman Story (1968) – as an indirect reference, as it were, to the person of the artist whom the film is about. The blind can also be seen – this time rolled up – on the wall behind the artist in Nauman’s Violin Film #1 (Playing the Violin as Fast as I Can) of 1967–68.

With its enigmatic poetry, the statement “The true artist is an amazing luminous fountain” has also inspired Nauman’s interpreters. Looking in depth at the artist’s life and work suggests that the words can be applied to Nauman himself. Coosje van Bruggen, for example, used the phrase as the title of her 1986 essay on Nauman as a draughtsman, and again in 1988 for a chapter of her informative Nauman monograph.26 Peter Plagens called his major 2014 biography Bruce Nauman: The True Artist.27 The literal aspect of the texts on the two window or wall signs receives less emphasis in the wealth of literature on Nauman, however, than their playful, ironic dimension. Thus van Bruggen, for example, writes that Nauman is here “playing with clichéd notions of what people believe an artist ought to do”28, while Neil Benezra considers that “Nauman was responding to his circumstances with idealism and irony in roughly equal measure.”29 Both of these comments are undoubtedly true to some extent and correspond to Nauman’s characteristic efforts to create a certain distance between himself and his own activity, so repeatedly called into question. Nevertheless, the seriousness of the statements on the two signs should not be underestimated. Brenda Richardson thinks it a mistake to consider “a statement of such idealized ambition […] facetious”.30 In her view, the “true artist statements are neither jocular nor romantic. It is correct to see the pieces as investigations of semiotics and also to read them as poetry […] But it is more to the point to focus on them as tests of the power of words, once vocalized or in this case visualized, to change the world. It is in this sense that the statements assume their most potent meaning and become, quite literally, political.”31 Against the backdrop of the 1960s, with its massive efforts to bring about social change, its nuclear armament as part of the Cold War and the USA’s traumatic involvement in the Vietnam War, it is indeed possible to read Nauman’s evocative statements as pointers towards impulses with whose aid a change of behaviour – and hence also of the state of affairs – might be wrought. Perhaps Nauman’s expectation that reading these texts would trigger a process of reflection was based on the vague hope of such an energising effect. Whatever the case, even the theory that artists might have the ability to spark insights that bring about change is itself a powerful motivation for action – at least for a young, not yet disillusioned artist.

The fact that Nauman made the “true artist” the subject of more or less public statements not once but twice, in 1966 and 1967 respectively, supports the assumption that the question of being an artist occupied him not just as a tongue-in-cheek starting point for primarily formal conclusions. During this period he developed further the idea of the artist as a luminous fountain, so that the neon spiral can be seen as a continuation of the Mylar shade in terms of content, too. The text of the spiral says what the true artist does, while the words on the blind tell us what he is. Putting the two together suggests the following conclusion: the ability of the artist to bring forth that which is surprisingly illuminating puts him in the position to discover hidden truths and, through his enlightening effect, to “help the world”. The word “luminous” no longer needs to appear in the spiral, since its luminosity has already become visible in the neon. We may even, if we wish, see further meanings in these two works: in the shape of the spiral, the artist’s doing symbolically extends in limitless fashion, while in the rectangle of the shade, the being-an-artist finds its conclusiveness in itself. In the Mylar shade, moreover, the timeless validity of the message is lent shape via the choice of an Antiqua typeface several centuries old. But of course interpretations must not be taken too far in order to demonstrate the complexity of these seemingly terse display signs.

Joan Simon raises an interesting point about The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain (Window or Wall Shade), namely the fact that Nauman wanted the work to activate a process of reflection: “As Nauman said about this piece and about a related neon that would soon follow, these words are like a test: when spoken aloud one must think about whether they are true.”32 In 1980, in conversation with Michele De Angelus, Nauman stated: “I think that you do things to find out if you believe in it in the first place, just like often you’ll say things in conversation, just to test, and so you do that. I think a lot of work is done that way, […] it’s the only way you find out is to do it.” And with regard to the two window signs: “Well, that was the examination, what is the function of an artist. Why am I an artist is the same question.”33 Here, at the latest, we come full circle from the anonymous “true artist” to Nauman himself.

Bruce Nauman has never ceased to examine the question of being an artist. Its existential significance is directly related to his motivation. In the beginning, he was still unsure whether and how he should explain what he was dealing with. In 1967, for example, when Joe Raffaele came to interview him in his studio and saw that he was working on a neon sign with words, he asked Nauman what it said. Nauman: “‘The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths.’” Raffaele, astonished: “And do you believe that?” Nauman: “I don’t know; I think we should leave that open.”34 To Brenda Richardson, many years later, Bruce Nauman said: “Once written down, I could see that the statement, The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths, was on the one hand a totally silly idea and yet, on the other hand, I believed it. It’s true and it’s not true at the same time. It depends on how you interpret it and how seriously you take yourself. For me it’s still a very strong thought.”35

The idea of the artist as a fountain challenged Bruce Nauman and he was reluctant to let it go. He explored it in various ways in photos, drawings, objects and sound. As if to test it, he illuminated it from all sides and thereby took it light-heartedly and seriously, literally and metaphorically. The theme appears for the first time in a 1966 colour photograph: under the title Self-Portrait as a Fountain, it shows a bare-chested Bruce Nauman with his hands raised as a bust spouting water.36 This humorous representation of the artist as a fountain was produced only shortly before the Window or Wall Shade and may be part of the reason why the latter’s enigmatic statement about the true artist was often understood as a loosely ironic comment on the role of the artist. For Nauman, however, the comedy of the image was probably also a means of intelligently concealing his ideas rather than laying them bare. Something similar can be said of Nauman’s 1967 photograph Bound to Fail, which takes the figure of speech literally and shows the artist in his cardigan seen from behind with his arms tied.37 The witty translation of language into image is an effective strategy to draw attention to a theme preoccupying the artist, and perhaps to prompt the viewer – after an initial grin – to embark on a deeper train of thought.

Self-Portrait as a Fountain, like the colour photographs that followed it, was produced in collaboration with the photographer Jack Fulton, who made the colour prints. Earlier in 1966 Fulton had already printed the enlargements for Nauman’s Flour Arrangements38, a seven-part series of photographs in which Nauman for the first time used photography as a means of alienation and in which he simultaneously documented – with remarkable understatement – the pioneering shift from an object-based understanding of art to one of art as process. Self-Portrait as a Fountain is the first in a group of eleven colour photographs that translate figures of speech into visual images in a seemingly simple – but in fact extremely sophisticated – manner. After some of the original prints (including Self-Portrait as a Fountain) were destroyed while in storage in New York, the image of Nauman as the gushing artist became more widely known via a portfolio, which the Leo Castelli Gallery published in 1970 on the basis of new reproductions in an edition of eight and which was subsequently much reproduced.39

Nauman’s pictorial representations of the artist as a fountain proceeded in parallel with his text-based treatments of the same theme. Shortly after the Window or Wall Shade, a black-and-white photograph of 1966–67 shows Bruce Nauman standing in a courtyard, half concealed behind plants, which he appears to be watering from his mouth. The title is The Artist as a Fountain. In her catalogue raisonné, Joan Simon situates the picture in direct relation to Nauman’s window shade, but also thinks that Nauman is playing in this photo “on the formality of public sculptures [and] on the idea of garden follies”.40 Coosje van Bruggen, too, acknowledges the photo’s subversion of the art-historical tradition of fountain sculpture, with its figures of mythological gods and goddesses. At the same time, she also draws a comparison, as other authors have done, with Marcel Duchamp’s provocative readymade Fountain (1917). This connection is suggested by the similar titles of the two works and their ironic distance from their subject, even though it becomes clear, upon closer inspection, that there are more differences than parallels between the intentions of the artists and the function of their works.41 A comparison of Nauman’s Window or Wall Shade with Jasper Johns’ Shade (1959), a painted window blind mounted on canvas, is similarly ambivalent. In Johns’ case, the result is a painting, in that of Nauman a linguistically charged object.42

Nauman also translated the idea of the artist as fountain figure in a 1967 drawing, in which he portrays himself as a stone nude with a jet of water spouting out of his mouth into a shallow basin.43 The figure’s pose captures the full energy of the process: his arms are bent at the elbow, like those of a runner, his head is tilted slightly backwards and his right foot is placed on the moulded rim of the fountain. The basin carries the inscription Myself as a marble fountain. As a gushing fountain carved in stone, the artist can indeed pour forth inspiration almost without limit. Perhaps this idea may even be understood as a subtle reference to the impact of the “true artist” beyond his own lifetime – comparable, in the broadest sense, with the Storage Capsules (for Henry Moore), in which Nauman pursued the idea of preserving the British sculptor, whom he considered undervalued by his younger contemporaries, for the future.44 In the case of the marble fountain, however, the role of the artist exerting a long-term effect is assumed, whether with suggestion or irony, by Nauman himself.

© Bruce Nauman / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Courtesy Sonnabend Collection and Antonio Homem.

Drawings are an important form of expression for Bruce Nauman in every phase of the creative process. Sometimes they serve the development of ideas, at others they record what Nauman has already developed, and at others again they contain instructions on the manufacture of his works. Drawing has certainly always been more a process of reflection and documentation than simply a random activity. For The True Artist is an Amazing Luminous Fountain (Window or Wall Shade), too, Nauman produced a drawing.45 It is an exact template for the typeface, the layout of the text and the spacing between the individual letters and words. On the blank interior of the paper, Nauman has written: “design for around the edge of a window or wall of these proportions”. The opportunity to implement this design presented itself for the first time in 1968, as part of the exhibition West Coast Art at the Portland Art Museum. Nauman had the letters of his “true artist” statement cut out of cardboard and painted by a professional sign painter, and mounted them around three sides of a gallery doorway, so that the visitors walked under the cryptic sentence as if under an archway. In this context Nauman also wrote the following instructions for installing the text as a border around rectangular surfaces:

“THE TRUE ARTIST IS AN AMAZING LUMINOUS FOUNTAIN / Is to be lettered on the perimeter of an existing architectural detail – on or around the perimeter of a window, a wall, a door or doorway, a floor, a room or a building… / Start lettering at the upper left (in the case of a vertical surface) and continue around the edges of the surface so that the bottom of the letters always face in (the letters on the bottom will be upside down) – in other words, preserve the direction of the sentence. Except where lettering around the edge of a doorway, with words on three sides only, try to make a closed figure with the sentence. / Lettering should be relatively anonymous Roman – not Italic – some thick and thin and small serifs. I can imagine a good job with script of some sort if you care to try. Words may be broken (please don’t hyphenate) to fit around corners. / Actual letter size will need to be adjusted to the length of the perimeter followed, and letters and word spacing. / If the sign is to be lettered in a non-English-speaking country, it may be translated and lettered in the appropriate language; or, it may be lettered in a language not of that country; or, it may be lettered in any language in any country. / The lettering should be black or silver and/or gold with blue or black shadow ground (as on a window) or some other color or combination of colors you might like.”46

These notes clearly reflect Nauman’s proximity to the contemporary art of the day, with its widespread conceptual approach and theoretical writings commenting upon the procedure. Nauman’s instructions allow a certain freedom of scope when it comes to the realisation of the piece, but at the same time limit this freedom so that there can be no doubt of the work’s final effect. Bruce Nauman is emphatic about limiting the influence of third parties and has repeatedly made clear that he does not understand his works as a playing field. He has thereby set himself against a trend whose aim was to activate the recipient by giving them a participatory role in the form of the artwork. Joan Simon, who reproduces Nauman’s instructions on Untitled (The True Artist is an Amazing Luminous Fountain) in her catalogue raisonné, additionally records that the painted letters were later collected in a paper bag and “recycled”, by Nauman’s friend and former teacher William T. Wiley, into a piece titled Beatnik Meteor (1970).47 Prior to this, in 1969, Nauman presented yet another version of his “true artist” sentence in cut-out letters at a group show at the Berkeley Gallery in San Francisco. Here he piled the blue and gold-painted letters in a corner, along with dust balls from the Whitney Museum, obtained for him by a gallery attendant.48 Only when arranged in the right order would the letters have formed the sentence from which they were taken. One might speculate as to their interpretation. The exhibition was called Repair Show and was organized by William Allan, whom Nauman knew, like Wiley, from his time in Davis and with whom he had already collaborated on several film projects.

Reproduced in: Joan Simon, ed., Bruce Nauman, Exhibition catalogue and Catalogue Raisonné, Minneapolis, Walker Art Center, 1994, no. 134, p. 230. © Bruce Nauman / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich.

Evidently the statement The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain from his Window or Wall Shade continued to preoccupy Bruce Nauman, for it resurfaced decades later in the context of large installations. In 2004 Nauman took on the difficult challenge of creating a work for the monumental Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London. He arrived at a dazzling solution, namely by reducing the hall to its basic architectural structure and filling it with the hum of sound. Twenty-two audio clips of Nauman texts and text fragments, spoken by different voices and drawn from works spanning over thirty years, issued from loudspeakers spaced at regular intervals down the two long sides. Among them, too, was the early statement The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain. Visitors felt themselves carried forwards by a wave of sound, from which the actual texts only emerged when they approached the loudspeakers. Nauman called the installation Raw Materials.49 He had created a cosmos of acoustic impressions and established a hypnotic mood; everything else took place in the minds of the recipients.

In 2009 Bruce Nauman represented the United States at the 53rd Venice Biennale. His installation of works from four decades earned the US Pavilion the Golden Lion for Best National Participation. (Nauman himself had already won an individual Golden Lion at the Biennale in 1999.) Around the exterior of the building, the names of the seven Vices and Virtues (1983–1988) lit up intermittently in the form of large, superimposed neon words – like a pointer to the moral value of art. Surrounding the main entrance to the pavilion, as if proclaiming its motto, was the aluminium lettering The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain. Glowing inside the building, and lending emphasis to the statement about the “true artist”, was the neon spiral The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (1967). In two editions of his Three Heads Fountain (2005), Nauman delegated the role of the sprinkling fountain to the epoxy resin heads of his friends and associates Juliet, Andrew and Rinde, from whose faces water sprayed into a large basin.50 In the context of the survey, Nauman’s ideas from the 1960s were not only present in retrospective form, but proved themselves thoroughly contemporary.

Studying Bruce Nauman leads almost inevitably to the conviction that the true artist is indeed an amazing luminous phenomenon. What the young Nauman first put forward as a hypothesis on a window blind in 1966, he himself subsequently confirmed. Almost no other artist of this period implemented as many illuminating ideas as he, without ever disclosing his credo as a yardstick. His “moral stance” was the motivation for works whose significance lies in their non-conformist translation of deeply felt truths. Nauman has triggered a long-term productive process with his repeated, existential self-interrogation and exercised a remarkable influence on the development of art with the wealth of his unique findings. The gushing fountain has set in motion a wide river.

1 Ian Wallace and Russell Keziere, Bruce Nauman interviewed, in: Vanguard 8, no. 1, February 1979, p. 18. The interview took place on 9 October 1978 in Vancouver, on the occasion of a Nauman show at Ace Gallery.

2 Joan Simon, Breaking the Silence: An Interview with Bruce Nauman, 1987, in: Art in America 76, no. 9, September 1988, pp. 140 – 149; quoted in: Janet Kraynak, ed., Please Pay Attention Please: Bruce Nauman’s Words. Writings and Interviews, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2005, p. 322.

3 Ibid., p. 327.

4 We may think, for example, of Nauman’s aggressive acoustic injunction Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room, 1968, and his crude Studio Version of Musical Chairs, 1983; see Joan Simon, ed., Bruce Nauman, exhibition catalogue and catalogue raisonné, Minneapolis, Walker Art Center, 1994; cat. rais. 113 and 315, pp. 132 and 288 respectively.

5 The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain (Window or Wall Shade), 1966; in: Simon 1994, cat. rais. 58, p. 206; technical details given in the title of this essay.

6 In an email of 13.7.2017 Bruce Nauman’s studio manager, Juliet Myers, confirmed on behalf of the artist: “He did not hang it [The True Artist is an Amazing Luminous Fountain (Window or Wall Shade)] in the front window of his San Francisco studio. However, his neon The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths was displayed in the window.”

7 A Rose Has No Teeth (Lead Tree Plaque), 1966, lead, 7 ½ x 8 x 2 ¼ in. (19.1 x 20.3 x 5.7 cm); in: Simon 1994, cat. rais. 52, p. 205.

8 Raw War, 1970, neon tubing, 6 ½ x 17 ⅛ x 2 ½ in. (16.5 x 43.5 x 6.4 cm); in: Simon 1994, cat. rais. 186, p. 248.

9 See e.g. One Hundred Live and Die, 1984, neon tubing on metal, 118 x 132 ¼ x 21 in. (299.7 x 335.9 x 53.3 cm); in: Simon 1994, cat. rais. 324, p. 290.

10 Coosje van Bruggen, Bruce Nauman, New York, Rizzoli International Publications, 1988, p. 14.

11 Jalal ad-Din Rumi (1207–1273) is also considered the founder of the Order of the Whirling Dervishes.

12 The expression “luminous poetry” is regularly found e.g. in reviews of Rumi anthologies.

13 The translations by Coleman Barks, in particular, led Rumi to become “the best-selling poet in the US”, according to Jane Ciabattari in the online article Why is Rumi the best-selling artist in the USA? of 21 October 2014 for BBC Culture (http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140414-americas-best-selling-poet; last accessed 06.12.17). Barks’s translations were only published as from the 1970s, however.

14 (author’s italics) The full text of Become a Sea runs: “Every form you see draws its origin from the unseen divine world. So if the form vanishes, what does it matter? Its origin was from the Eternal. Do not grieve that every form you see, every mystical truth you hear will one day vanish. The Fountain is always gushing water. Neither Fountain nor water will ever stop flowing, so why mourn? Your spirit is a fountain; river after river flow from it, put all mourning out of your mind forever and keep on drinking from the water. Do not be afraid. The water is limitless.” Rumi, Odes / Become a Sea, in: Andrew Harvey, ed., Teachings of Rumi, Boston, Shambhala, 1999, p. 166.

15 The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967, neon tubing, 59 x 55 x 2 in. (149.9 x 139.7 x 5.1 cm), edition of 3 + AP; in: Simon 1994, cat. rais. 92, p. 216.

16 Sol LeWitt, Sentences on Conceptual Art, in: Art-Language I/1, May 1969, sentence no. 1. Marco De Michelis also points to these parallels in his essay Spaces, in: Carlos Basualdo; Michael R. Taylor, ed., Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens, Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009, p. 66.

17 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, in: Artforum, V/10, June 1967.

18 Ibid.

19 Brenda Richardson, Bruce Nauman: Neons, exh. cat., Baltimore, The Baltimore Museum of Art, 1982, p. 22.

20 See Simon 1994, The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain (Window or Wall Shade), cat. rais. 58, p. 206.

21 Michele de Angelus, Oral history interview with Bruce Nauman, 27 – 30 May 1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, transcript p. 23.

22 Richardson 1982, p. 20.

23 See e.g. ibid.; Neal Benezra, Surveying Nauman, in: Simon 1994, p. 22; and Joan Simon in ibid., entry on cat. rais. 92, p. 216. See also note 6.

24 Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Kounellis, Merz, Nauman, Serra; Arbeiten um 1968, 15.03. – 26.04.1981; reproduced on p. 25 of the exhibition catalogue.

25 De Angelus 1980, transcript p. 23.

26 Coosje van Bruggen, The true artist is an amazing luminous fountain, in: Bruce Nauman Drawings / Zeichnungen: 1965 –1986, exh. cat., Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, 1986.

27 Peter Plagens, Bruce Nauman. The True Artist, London, Phaidon, 2014.

28 van Bruggen 1988, p. 15.

29 Neal Benezra, Surveying Nauman, in: Simon 1994, p. 22.

30 Richardson 1982, p. 20.

31 Ibid., p. 22

32 Simon 1994, cat. rais. 58, p. 206.

33 de Angelus 1980, transcript p. 15.

34 Interview by Joe Raffaele, extract from the article The Way-Out West: Interviews with 4 San Francisco Artists by Joe Raffaele and Elizabeth Baker, in: ARTNews 66, no. 4, summer 1967.

35 Richardson 1982, p. 20.

36 Self-Portrait as a Fountain, 1966, colour photograph, 18 ¾ x 23 ½ in. (47.6 x 59.7 cm), destroyed; Simon 1994, cat rais. 54, p. 205.

37 Bound to Fail, 1967, colour photograph, 19 ½ x 23 in. (49.5 x 58.4 cm), destroyed; Simon 1994, cat. rais. 72, p. 210.

38 Flour Arrangements, 1966, seven colour photographs, dimensions variable; Simon 1994, cat. rais. 42, p. 202; see also Christel Sauer’s text Flour Arrangements, 2017/18.

39 Untitled (Set of Eleven Color Photographs), 1966–67; including Bound to Fail (see note 38); destroyed. Eleven Color Photographs, 1966–67/1970, portfolio of eleven colour photographs of various dimensions, published in an edition of 8 by the Leo Castelli Gallery, ed., New York; Simon 1994, cat. rais. 175, p. 242. The majority of the portfolios were broken up into single photographs.

40 The Artist as a Fountain, 1966 – 67, black-and-white photograph, 8 x 10 in. (20.3 x 24.5 cm); Simon 1994, cat. rais. 71, p. 209.

41 van Bruggen 1988. p. 14.

42 Jasper Johns, Shade, 1959; encaustic on canvas with objects; 52 x 39 in. (132 x 99 cm). Neal Benezra, for example, refers to Johns’ work in connection with Nauman’s Window or Wall Shade in his essay: Surveying Nauman, in: Simon 1994, p. 22.

43 Myself as a Marble Fountain, 1967, ink and wash, 19 x 24 in. (48 x 60.5 cm); in: Bruce Nauman Drawings / Zeichnungen: 1965 –1986, exh. cat., Basel 1986, no. 49, fig. 30.

44 See e.g. the drawing Storage Capsule for Henry Moore Made of Metallic Plastic, 1966, coloured pencil, 40 x 35 in. (101.6 x 88.9 cm); in: Bruce Nauman Drawings / Zeichnungen: 1965 –1986, exh. cat., Basel 1986, no. 31, fig. 17. Nauman explored the idea of storage and conservation in a series of works.

45 The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain, 1966, graphite and black ink, 24 x 19 in. (61 x 48.2 cm); in: Bruce Nauman Drawings / Zeichnungen: 1965 –1986, exh. cat., Basel 1986, no. 17, fig. 28.

46 Untitled (The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain), 1968, cut-out letters; Simon 1994, cat. rais. 134, p. 230.

47 Ibid.

48 Untitled, 1969, cut-out letters, dust, dimensions variable; Simon 1994, cat. rais. 159, p. 237. In 1969 Nauman took part in the exhibition Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. The dust balls probably date from this time.

49 Raw Materials, 2004, sound installation (21 channels), display dimensions variable. First installation at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London, 12.10.2004 – 2.5.2005. From 15.5. – 20.8.2017 the work was installed there for a second time.

50 Three Heads Fountain (Three Andrews), 2005, and Three Heads Fountain (Juliet, Andrew, Rinde), 2005, fibreglass and epoxy resin, wire, clear hoses, submersible pump, rubber lined basin, water.

Translated from German by Karen Williams

© 2017 Christel Sauer / Raussmüller