“We offer artists who want to create a large-scale work, but who lack the means to do so, materials and tools, spaces, assistants and information […]. Above all, however, I hope to be able to offer the artists who work here interest. […] In order that our artists feel sustained by the interest of others, InK needs a public. A public that keeps coming by, so as to get a picture what’s currently going on; a public that cares about the genesis of the work and is not afraid to start a discussion with the artist working on it.”1

Urs Raussmüller spoke these words in 1978 in an interview with the Tagesanzeiger Swiss daily newspaper, published one day ahead of the opening of “InK. Halle für internationale neue Kunst” in Zurich. With InK as an innovative concept in art patronage, Raussmüller was about to embark on a remarkable experiment with art and society. What results it would yield was at that point, admittedly, entirely open – but the initiator’s motivation was clear and determined, and so, too, was his firm conviction that it was necessary to proceed differently than hitherto with the new art now being made, and that artists, in order to be productive, needed a supportive environment which created opening and facilitated the exchange between artists, works and recipients. A concept with such a broad compass did not yet exist.

Raussmüller knew exactly what he was talking about. As an artist, he had himself been confronted by the fact that the patronage of young art makers was often confined simply to a monetary contribution, and that at the crucial moment – when artists were buzzing with ideas and needed materials, space and assistance to experiment with and implement new concepts – they were left to their own devices. With InK, Raussmüller countered this concept of art patronage with one that was at last comprehensive. It started resolutely from the artist and the creation of art, but thereby never excluded the opposite party, in other words the public. On the contrary, it incorporated this latter actively into the artistic processes of creation, so that barriers between artists and public were overcome and an exchange could take place on equal terms.

What manifested itself with InK exactly forty years ago on 15 June 1978, also signalled a new chapter in Urs Raussmüller’s work. It was the prelude to a series of pioneering art institutions: the Hallen für Neue Kunst in Schaffhausen, RENN Espace in Paris, and Casino Luxembourg. Despite their differences, they all started from one and the same premise: it must be possible for art to be directly experienced. The spatial situations and innovative art mediation concepts that each put in place were born out of the conviction that powerful works of New Art – when brought together in a spatial context with appropriate regard to lighting and each other – are able to inspire creative action far beyond themselves. With the current expansion of the Raussmüller Hallen in Basel as a workplace with artworks, this conviction is finding yet another practical expression.

In this context, a look back at the ground-breaking nature of InK and its concept seems highly topical. In her text, Christel Sauer – who was involved from the outset – traces the remarkable path travelled by InK, the artists, art and society in the Zurich of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Her essay was first published in 2012 in the Swiss art magazine DU with the title “Zeichen und Wunder: das InK in Zürich” (Signs and Miracles: InK in Zurich) and appears here in slightly abridged form.

InK. Halle für internationale neue Kunst

by Christel Sauer

Photo: © Raussmüller

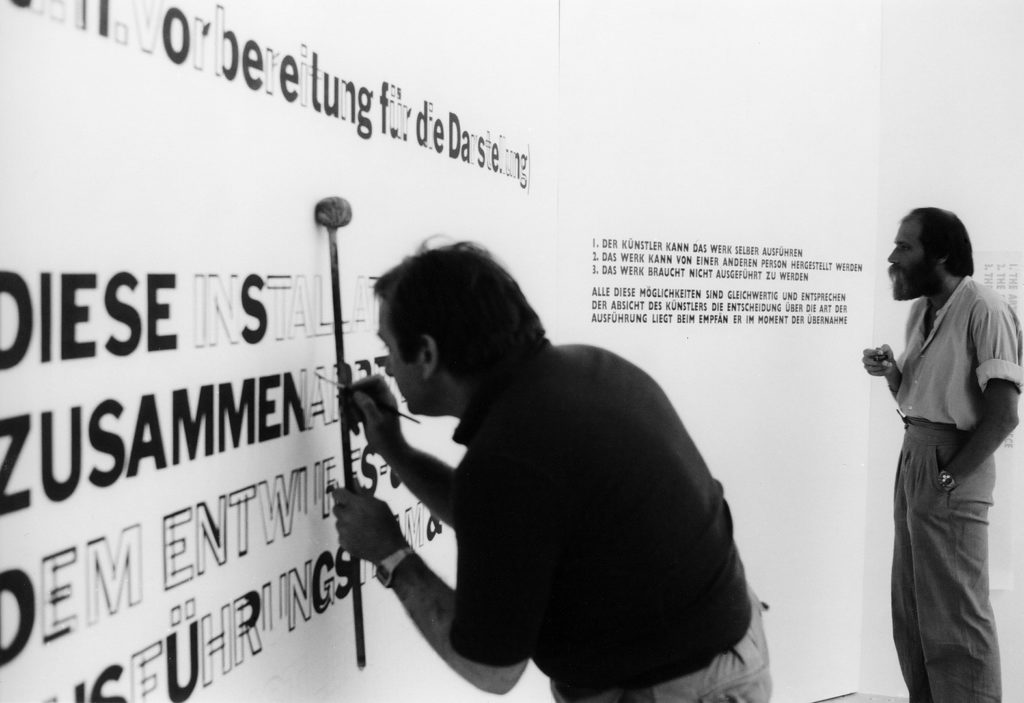

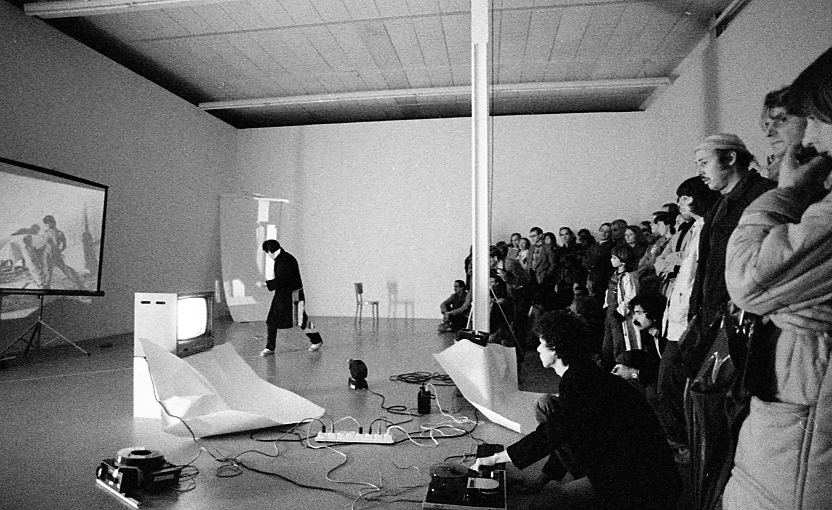

What does “InK” stand for? It is the abbreviation for “Halle für internationale neue Kunst” (“Hall for international new art”). Strictly speaking, therefore, it ought to be “HinK”, but that didn’t have quite the same appeal and so we called the institution “InK”. InK existed from 1978 to 1981. During this time we carried out some sixty exhibitions with eighty-two artists – along with actions, concerts with musicians such as Steve Reich, poetry readings with John Giorno, Hans Carl Artmann and Gerard Malanga from Warhol’s Factory, film screenings, lectures and discussions. John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha and Lawrence Weiner took plenty of time over their works at InK, relishing its creative freedom. Jonathan Borofsky painted walls and ceiling with abandon – his first installation in Europe. Hanne Darboven filled all the spaces with a political manifesto, and we showed secretly exported paintings and sculptures by A.R. Penck, the East German artist denigrated by the GDR regime. Hans-Peter Feldmann devoted the first issue of his newspaper Image to the InK exhibition and Sigmar Polke presented a performance that turned seamlessly into uproar and later assumed all the traits of a legend.

© Lawrence Weiner / 2018, ProLitteris, Zürich. Photo: © Raussmüller

The response to InK was great – albeit not in Zurich, at that time little interested in art. In Holland, by contrast, which was then at the cutting edge of new art, and in Germany and the USA, artists and art lovers reacted with keen interest to an art institution for which there was no precedent. The model of an exemplary form of art patronage had been implemented not in Basel or Bern, but in sedate Zurich, of all places. This patronage started from the needs of the artist and incorporated society. InK was open daily and admission was free. The gallery was simultaneously a studio and a meeting point, the site of exhibitions and artistic actions. Since the installations rarely all ended at the same time, they regularly found themselves overlapping and in new contexts. Artists such as Robert Ryman and Bruce Nauman – today heroes of art history – met each other here and conversed with visitors. A lively, creative atmosphere prevailed; the artists were inspired and the viewers curious. In its form and content, InK was truly an innovation.

The history of InK is linear and – sadly – brief. It started with the invitation from Arina Kowner, the head of the Directorate of Cultural and Social Affairs at the Federation of Migros Cooperatives (FMC), to artist Urs Raussmüller to exhibit his works in the freshly renovated foyer of the old administrative building on Limmatplatz. Raussmüller argued against this form of exhibition and was subsequently appointed as a consultant to advise on new strategies for the FMC’s Fine Arts division. He proposed providing funding for artists right from the production stage – a concept that won the support of CEO Pierre Arnold. Artists who had something to communicate should receive all the means necessary in order to be able to make and present works without commercial considerations.

Raussmüller’s proposal corresponded to the sort of patronage he would have wished for himself: an opposite party who was interested in new art; a fee that made it possible to turn artistic ideas into reality; a location where the resulting works could be publicly shown, and if necessary also made; and lastly recipients who responded to the works – insofar as they were convincing – by buying them.

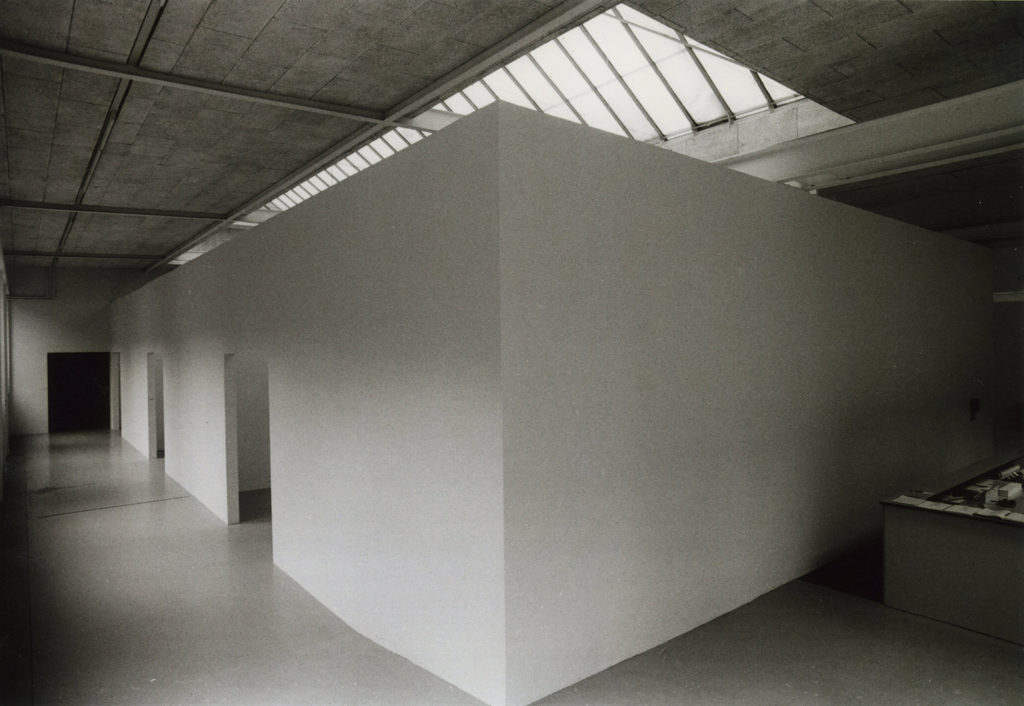

Photo: © Raussmüller

In retrospect, it is a small miracle that Raussmüller was able to implement his concept without having any major conditions imposed. He soon found a building with a floor area of some 600 square metres at Limmatstrasse 87. It was part of the former Reishauer machine-tool factory and was ideally located between the FMC’s head offices and Zurich main station – in the immediate vicinity of the School of Applied Arts, whose students would subsequently become the new institution’s keenest visitors. Within just a few weeks Raussmüller had transformed the factory wing into a consummate exhibition gallery. Subdivided by white-painted walls, it comprised four large rooms and a wide corridor with windows running the full length of the façade. Saw-tooth roofs provided three of the rooms with natural light from above, while the fourth received incidental light. There was a large entrance with a reception desk and information stand, and ancillary rooms for artists to work in. InK became the model for the transformation of an industrial building into a site for art.

We opened InK on 15 June 1978. Jannis Kounellis made a suggestive installation out of sound and soot, and Robert Ryman created a new group of paintings for the occasion. With this strong start, an extremely active programme began. The FMC granted InK an annual budget of half a million Swiss francs for its activities. The artists took advantage of the opportunity far beyond our expectations and with impressively creative projects. In the majority of cases they confined themselves to one room, but occasionally the whole of the interior, including the corridor and entrance lobby, became an exhibition space. This was the case with the installations by young Swiss artists, with thematic exhibitions (Poetische Aufklärung in der europäischen Kunst der Gegenwart… and With a Certain Smile?) and the large-scale shows by Bruce Nauman and Robert Ryman, which premiered at InK before embarking on international tours.

© Robert Ryman / 2018, ProLitteris, Zürich. Photo: © Raussmüller.

Today most of the artists of the InK era are represented in museums around the world, and the activities of that time seem fairly normal. But at the end of the 1970s this art was new and largely unknown. We are glad that the Federation of Migros Cooperatives responded to the proposal from InK and – by acquiring works suggested by Urs Raussmüller – laid the foundations of an important collection. And one can only be amazed at the low prices back then. We are also glad that we created an enduring record of the exhibitions in the InK-Dokumentationen series (numbers 1 to 8), which focused specifically on the installations in photographs and texts. These publications represented what was then a new form of art mediation and today bring a slice of art history vividly to life before our eyes. We commissioned the texts increasingly from students, who thus came into closer contact with the artists and became familiar with an art with which the universities still had nothing to do. The creative Patrick Frey was one of our team, as were Dieter Hall, who then began painting himself, Peter Blum, the New Yorker gallerist, university lecturer Laura Arici and many others. As one can see: the history of InK’s influence has yet to be written…

After not quite three years, on 31 March 1981 we had to close InK down again. Its ending is a sorry tale, since it affected not only a tremendous institution but also the Federation of Migros Cooperatives, which was subsequently no longer available to provide this form of sponsorship. A Zurich city councillor had ambitions of becoming mayor and needed a prestigious project. As head of the local education authority, he conceived the idea of establishing a vocational college in the former Reishauer factory. We fought to retain the separate InK wing, which would have married very happily with the school, and within the FMC, too, efforts were made – despite internal resistance – to secure the continuation of its innovative arts patronage. The battle was ostensibly won by the city, however: the college was built and the new mayor elected, but our InK disappeared.

The final exhibition at InK was Das Kapital Raum 1970–1977. It had originally been Raussmüller’s intention to construct a permanent room for Joseph Beuys in the InK wing and to connect the work with InK. The developments in local politics then made this impossible. What resulted instead was a rudimentary installation, through which Beuys conveyed his indignation at the temporary presentation of objects with which he planned to erect a “monument”. Raussmüller was supposed to create the room for him – which he then did in 1983/84 with the Hallen für Neue Kunst in Schaffhausen. In Zurich this work did not happen. And when the city terminated the FMC’s lease on the factory wing, it went so far as to demand that Raussmüller’s exhibition structure should be destroyed.

© Bruce McLean / 2018, ProLitteris, Zürich. Photo: © Raussmüller.

The InK years were also the time of the so-called youth unrest. It erupted in Zurich much later than in other European cities. People were already wondering why protest was so slow in coming, since there was no shortage of reasons for it. The use of certain terms was one: suddenly everything that was not middle-of-the-road was alternative. This word marked a freshly drawn divide between law-abiding citizens and – thus the perception – radical non-conformists: “die Alternativen” stood for a chaotic element that needed to be kept in check. And the more this happened (I recall the phalanxes of police with their riot shields and rubber bullets, which came right into InK), the more “die Alternativen” appeared as a threat.

With our initiative for new art, we, too, were assigned to “die Alternativen”. Once the closure of InK was definite, the city councillor responsible went so far as to offer us, by way of a substitute, the Autonomes Jugendzentrum (“Autonomous Youth Centre”) behind the railway station. From the city’s point of view, getting rid of this trouble spot – a meeting point for Zurich’s rebellious youth – by giving it an “alternative” new purpose would have been an excellent solution.

We preferred to take our leave of Zurich. We had long been seeking premises that would allow us to resume and continue InK’s activities. Back then, however, the industrial buildings in Zurich were still in use. Properties that became free, such as the former flower market on Hafnerstrasse, sold to developers for high prices on account of their location and thus quickly moved beyond our reach. The redevelopment of buildings in the Escher-Wyss and Löwenbräu districts, in the today flourishing Zürich-West part of town, was strictly prohibited by the building regulations then in force.

© Sol LeWitt / 2018, ProLitteris, Zürich. Photo: © Raussmüller

We therefore increasingly looked outside Zurich, although here, too, our options were limited. Unused factory halls of the kind we wanted were still a rarity and their conversion into spaces for art an alien concept. Rethinking with regard to structures and activities was still in its infancy – while at the same time the boom in ambitious architect-designed museums was beginning. And so we widened our search ever further, until in spring 1982 we came across the Schoeller textile factory standing empty in Schaffhausen. Thus began a new chapter: the Hallen für Neue Kunst. The Hallen in Schaffhausen was a consequence of InK and at the same time an extension. With its exhibition surface area of 5,500 square metres, it represented a vast expansion. Here Urs Raussmüller could offer important works of New Art what the traditional museums of the day could not, and what large-scale installations, after a phase of experimentation, most needed: space and time for their effect. After the fast-paced rhythm of the activities at InK, the Hallen thus became a place of reflection, as it were.

With the concept underpinning its content and architecture, the Hallen für Neue Kunst likewise served as a model. It was the first holistic transformation of a factory building into an art museum and exerted a worldwide influence. The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the Tate Modern in London and Dia:Beacon in upstate New York all took their cue from the Hallen. Drawing upon his experience at InK, Raussmüller allowed art and space to forge a generous alliance. The result was considered a cultural manifesto – a “museum in the spirit of its artists”.

In 2014, after thirty years in Schaffhausen, Raussmüller closed the Hallen für Neue Kunst and relocated the activities of his organisation to Basel.

08.06.2018

1 Urs Raussmüller in the interview “InK: Der neue Ort für neue Kunst”, Tagesanzeiger newspaper, 14.06.1978.

© 2012/2018 Christel Sauer / Raussmüller